Explosion Under the Microscope

Thanks to the unique properties of palladium, scientists have, for the first time, observed the water-formation reaction at the atomic level. This breakthrough marks the beginning of refining a technology that can produce water from oxygen and hydrogen—the two most abundant substances in the universe. Once perfected and commercially implemented, this technology could address freshwater shortages in arid regions.

Imagine densely populated areas in India or Egypt suffering from extreme heat and severe drought. In such regions, where dehydration threatens millions, a mobile device arrives and starts producing water directly from the air—even without access to electricity. The only requirement? A cylinder of hydrogen.

This may sound like science fiction, but researchers from Northwestern University in the U.S. have made significant progress in water production from hydrogen and oxygen using a palladium catalyst. For the first time, scientists observed water molecules forming at the atomic scale through transmission electron microscope. The application of this technology could revolutionize access to a critical resource—freshwater—especially in extreme conditions such as in space, arid regions, or uninhabited islands.

At first glance, water formation might seem straightforward: hydrogen and oxygen, two ubiquitous substances, react to produce water – a process that has occurred in the universe since its earliest days. However, hydrogen oxidation is an explosive reaction that occurs only within a specific concentration range (4-75% hydrogen in air) and extremely high temperatures and pressures. Pure hydrogen burns with a characteristic soft “pop” sound, while a 2:1 mixture of hydrogen and oxygen, known as “detonating gas,” ignites with a violent explosion. Under ideal conditions, hydrogen combustion can reach temperatures of up to 2000°C. Although water forms during the process, it instantly evaporates into steam, leaving behind only heat. Managing this heat is another significant challenge.

Adding a catalyst like platinum or palladium solves the explosion problem by enabling a process called catalytic oxidation. Palladium’s unique properties allow this reaction to occur under normal conditions, without extreme temperatures or pressures. Furthermore, the process generates electricity as a byproduct. Theoretically, 1 kilogram of hydrogen can produce 9 liters of water, making the cost of such water viable. As hydrogen production becomes more affordable, this method could address localized freshwater shortages—a vital resource of the 21st century.

Glass Nanoscale Honeycombs Under an Electron Microscope

The reaction of catalytic hydrogen oxidation (non-explosive water formation) has been known for a long time. As early as the 1900s, researchers discovered that palladium and platinum could serve as catalysts for such processes. However, the mechanism behind this reaction remained elusive for decades. Palladium’s use as a catalyst in hydrogenation and oxidation reactions gained momentum in the early 20th century. The hydrogen oxidation reaction producing water on palladium surfaces has been studied extensively, yet the finer details of the process remain under investigation due to the complex atomic interactions influenced by temperature and pressure.

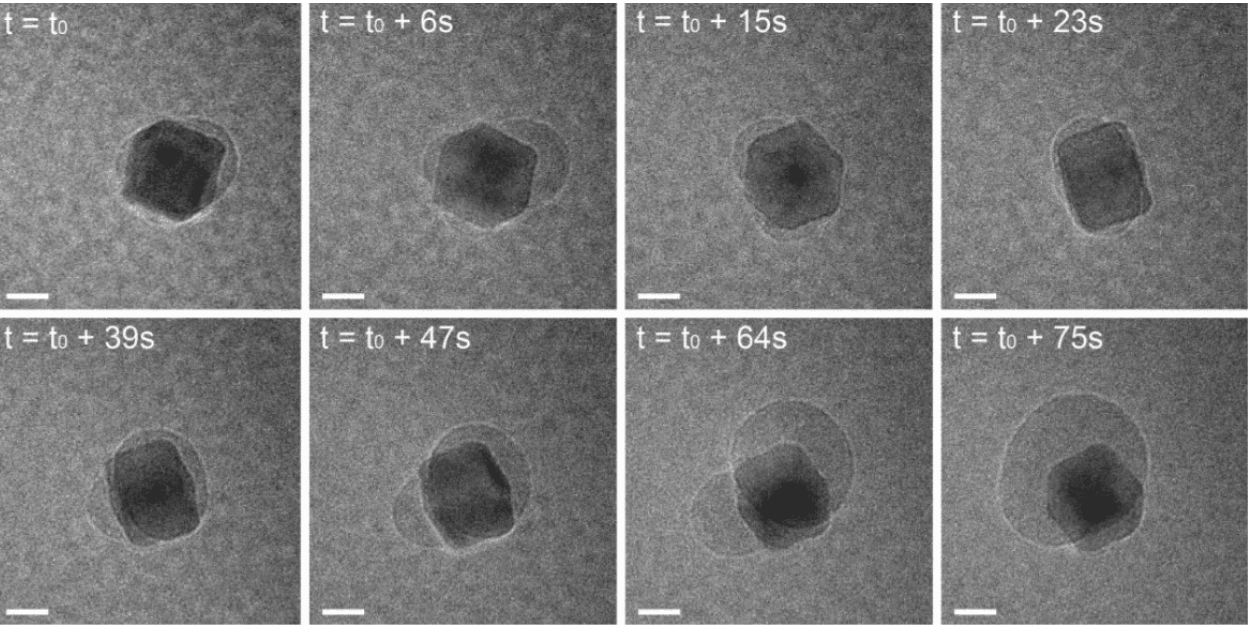

Scientists at Northwestern University developed a technology to observe this reaction at the atomic level in real time using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). This breakthrough provided insights into the underlying mechanisms of water formation from hydrogen and oxygen. By leveraging TEM capabilities, researchers were able to monitor nanoscale processes with unprecedented precision.

Using this technology, scientists first observed how hydrogen atoms penetrate the metal’s structure, expanding its cubic lattice. Upon introducing oxygen into the microreactor, the hydrogen atoms began returning to the palladium surface, where tiny water bubbles formed.

We believe this might be the smallest bubble ever observed directly. It wasn’t what we expected. Luckily, we recorded it to prove we weren’t imagining things.

Dr. Yukun Liu, one of the researchers in Professor Vinayak Dravid’s lab at Northwestern University

To analyze the bubbles, the team employed electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS), which confirmed the presence of water molecules by detecting their characteristic bond energies. They further validated these findings by heating the bubbles to assess their boiling point.

Until recently, observing such processes at atomic precision was impossible. In January 2024, a new method for real-time gas molecule analysis was developed. The method involves an ultrathin vitreous membrane that traps gas molecules inside honeycomb-shaped nanoreactors, allowing them to be studied in high-vacuum TEMs. This technological leap unveiled a previously hidden world, offering scientists new insights into the intermediate stages of chemical reactions between hydrogen and oxygen.

The second stage of the study was to assess how to optimise the process. To do this, the researchers added oxygen and hydrogen separately in different orders to determine in which sequence water formed fastest. The results showed that the rate of palladium-catalysed hydrogen oxidation was significantly affected by the sequence in which the gases were added. Adding hydrogen first resulted in the fastest reaction.

The hydrogen molecules broke up into atoms, which, being very small, easily penetrated the palladium lattice. When oxygen molecules were added, the hydrogen atoms ‘popped’ out of the palladium and reacted with them. The palladium would then shrink back to its original state. Although oxygen atoms also interact with palladium, they are too bulky to penetrate its crystal lattice. When oxygen is introduced first, it coats the surface of the palladium like a film, preventing hydrogen from absorbing and starting the reaction.

Universal “Miracle”

By visualizing water formation on the nanoscale, we were able to identify the optimal conditions for rapid water production under ambient conditions. These findings have practical implications, such as producing water in deep space using gases and metal catalysts, without requiring extreme reaction conditions.

Professor Vinayak Dravid, senior co-author of the study

While the technology’s practical application holds promise, experts have raised questions about its feasibility. For instance, the cost of transporting hydrogen to remote areas could be prohibitive, necessitating further economic analysis. Nevertheless, the study’s authors believe that producing water from simple gases like hydrogen and oxygen, using a reusable palladium catalyst, could have a significant impact in certain scenarios. The technology is particularly promising for areas requiring water under extreme or remote conditions—deserts, space, or uninhabited islands with no access to freshwater.

The researchers assert that scaling this technology could lead to new methods of water production. One speculative scenario involves infusing hydrogen into palladium sheets, loading them onto spacecraft, and using them to generate drinking water during long space missions. However, water scarcity is not limited to space exploration; it remains a pressing issue on Earth. Currently, billions of dollars are being invested in freshwater production technologies. For instance, startups like Uravu Labs are developing air-to-water systems using desiccants, but these methods require processing large volumes of air, heating moisture, and condensing it—processes that demand significant energy input, which may not be available in disaster-stricken regions.

Producing water from hydrogen and oxygen, unlike other chemical processes that consume significant resources or generate waste, requires no electricity. Palladium is reusable and recyclable, making it a sustainable option. Hydrogen—the sole consumable resource in this new technology—is the most abundant element in the universe, although rare in its free form on Earth. Crucially, global hydrogen production and transportation technologies are rapidly advancing. At present, a kilogram of hydrogen costs $3-4, with prices expected to decline as production scales.

As hydrogen energy solutions evolve, humanity may have the chance to address localized water shortages. Palladium-catalyzed water production could potentially be integrated into water-intensive industries in remote or resource-scarce areas. With ongoing research, further refinements and applications of this groundbreaking technology are anticipated. It is hoped that producing water from air using palladium and hydrogen will not only represent a scientific milestone but also offer solutions to some of today’s ecological and resource challenges.

Source: https://news.northwestern.edu/stories/2024/september/watch-water-form-out-of-thin-air/

Ivanhoe Mines, a Canadian mining and exploration company known for several high-profile discoveries, has driven underground development into the high-grade Platreef orebody for the first time. The company’s Executive Co-Chair Robert Friedland and President and Chief Executive Officer Marna Cloete detailed the breakthrough, with mining crews entering the orebody at the 850-metre level with the first blast of high-grade ore in early May.

Canadian exploration company Power Metallic has reported results from its deepest intersection to date at the Lion Zone, carried out in the wake of successful exploration activities last year. The 2024 discovery of the zone, 5.5 kilometres away from the Nisk Main Zone, has shifted the company’s focus towards what could prove a game-changing discovery.

Australian mining company Southern Palladium has received an environmental authorization (EA) on its flagship Tier 1 Bengwenyama project from South Africa’s Department of Mineral and Petroleum Resources (DMPR). The license outlines rights on underground mining and related infrastructural activities on the project, marking a key milestone towards development.

A study from a team of chemists working at McGill University in Montreal, Canada has proposed a new method for synthesising palladium catalysts using electrochemical potential, supporting both oxidative addition and reductive elimination with two-electron exchange in mild temperature and pressure conditions.

A team of functional materials researchers in China developed a copper–palladium catalyst that has been shown to improve catalytic activity and selectivity in the electrochemical nitrate reduction reaction (NO3RR), leading to improved ammonia yields. Scaling this process could significantly reduce the energy and environmental burden of the ammonia industry as a whole.

Zhe Gong et al. from the China University of Geosciences and Zhiping Deng and Xiaolei Wang from the University of Alberta (Canada) have developed a highly efficient palladium catalyst that could support the large-scale rollout of hydrogen fuel cells. The catalyst was designed by doping palladium with cobalt producing atomic cobalt (Co)-doped Pd metallene (Co-Pdene), and demonstrated exceptional electrocatalytic performance while maintaining its structural integrity.