Chemistry

Structure: Electron shell

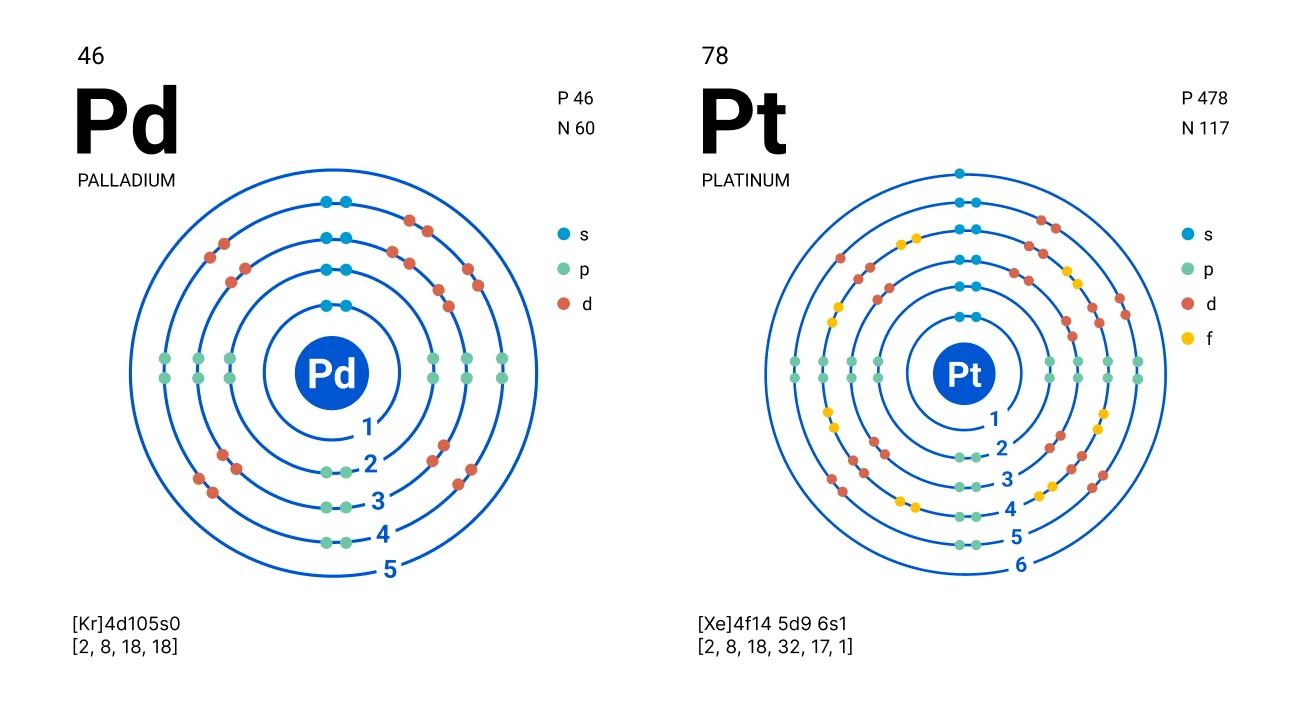

The distinctive properties of palladium are rooted in the unique configuration of its outer electron shell, which is distinct from that observed in other transition metals. Palladium stands out as the sole member of the d-block elements that exhibits a fully occupied outer shell. Typically, transition metals possess one or two electrons in their outer shell. In palladium, however, both electrons from the 5s orbital ‘slipped’ to the lower 4d orbital, as depicted in Figure 1.

The configuration of the outer electron shells is pivotal in determining the manner in which atoms combine into molecules and their behaviour in reactions with other elements or molecules. The high inertness of palladium is attributed to the full occupation of the 4d level and the empty 5s level, while its increased activity in chemical reactions compared to other platinoids is attributable to the presence of these two levels.

Structure: Crystal lattice

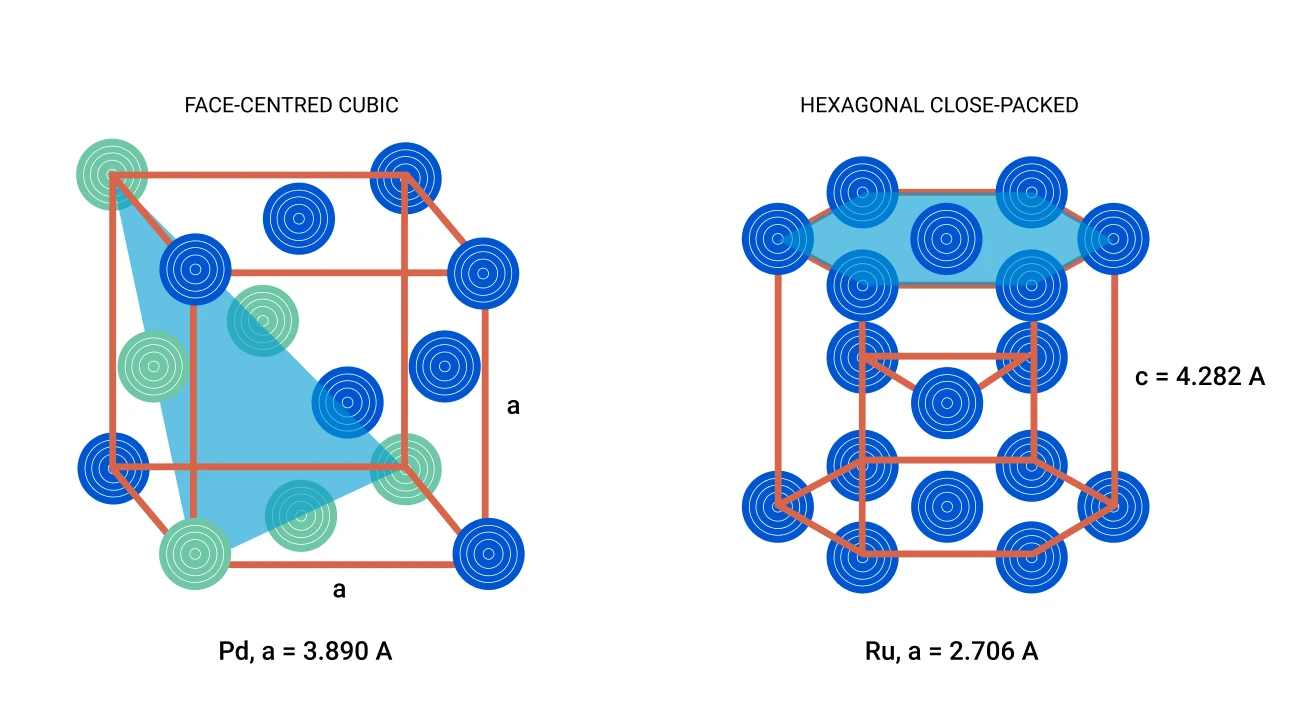

Palladium atoms form crystals with the so-called face-centred cubic lattice (FCC) (Fig. 2). This type of crystal lattice is characteristic of many metals, including several in the platinum group. An important feature of the crystal lattice of palladium is the larger distance between atoms compared to other platinoids.

Properties: Chemical

Palladium has strong catalytic properties due to the incompleteness of the d shell electrons. The exchange of electrons between the d shell and the outer s shell, characterised by the work of the electron yield, leads to the appearance of free valences on the surface, which determine, among other things, the adsorption (chemisorption) properties of transition metals and metals of the platinum group.

Chemical properties

| Property | Pd | Pt | Ru | Ir | Rh | Os |

| Atomic number | 46 | 78 | 44 | 77 | 45 | 76 |

| Atomic weight | 106.4 | 195.09 | 101.07 | 192.22 | 102.9055 | 190.2 |

| Crystal lattice* | FCC | FCC | HCP | FCC | FCC | HCP |

| Lattice parameters | ||||||

| a, Å | 3.890 | 3.850 | 2.706 | 3.840 | 3.803 | 2.734 |

| c, Å | – | – | 4.282 | – | – | 4.317 |

| Electron configuration | 4d10 5s0 | 4f14 5d9 6s1 | 4d7 5s1 | 4f14 5d7 6s2 | 4d8 5s1 | 4f14 5d6 6s2 |

| Electron yield work, eV | 5.22–5.6 | 5.12–5.93 | 4.71 | 5.0–5.67 | 4.98 | 5.93 |

| Oxidation degrees | +2, +4 | +2, +4 | +3, +4, +6, +8 | +3, +4, +6 | +3 | +4, +6, +8 |

| Poling electronegativity | 2.2 | 2.28 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.28 | 2.2 |

| First ionisation energy, eV | 8.3369 | 9.0 | 7.3605 | 9.1 | 7.4589 | 8.7 |

| Second ionisation energy, eV | 19.43 | 18.563 | 16.76 | N/A | 18.08 | N/A |

| Third ionisation energy, eV | 32.93 | N/A | 28.47 | N/A | 31.06 | N/A |

| Electronic affinity, EA/kJ · mol−1 | 53.7 | 205.3 | 101 | 151 | 109.7 | 106 |

| Standard electrode potentials E0, В | +0.987 | +1.190 | +0.45 | +1.017 | +0.8 | +0.7 |

* FCC – face-centred cubic, HCP – hexagonal close-packed

highest value, lowest value

The ability of palladium (Pd) to catalyse oxidation reactions has defined its primary application area, which is the automotive industry – specifically catalytic exhaust gas neutralisation systems. The production of catalytic converters now accounts for the majority of global palladium consumption. The employment of palladium in combination with other platinum group metals (PGMs), such as platinum (Pt) and rhodium (Rh), within three-component catalysts facilitates the chemical conversion of the primary harmful exhaust components – carbon monoxide (CO), hydrocarbons (HC) and nitrogen oxides (NOx) – into water, carbon dioxide (CO2) and nitrogen (N2), thereby providing an effective solution to enhance the environmental performance of internal combustion engines.

The remarkable sorption capacity of palladium for hydrogen has been instrumental in its recognition as a catalyst of choice in hydrogenation and de-hydrogenation reactions. The development of palladium-based catalysts has enabled highly selective reactions, thereby minimising the yield of undesirable byproducts. The field of catalysis has witnessed the advent of catalysts comprising palladium in the form of particles or alloys, along with organometallic catalysts for homogeneous processes, exemplified by phosphine complexes employed in cross-coupling reactions. In 2010, the prestigious Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded for the development of chemical catalytic reactions (cross-coupling reactions), which enable complex branched molecules to be assembled from simple carbon compounds as if they were Lego blocks. The products of these reactions are used in all branches of industry, and they are of particular importance for medicinal chemistry.

The catalytic properties of palladium thus determine its application in various branches of the chemical industry. Specifically, in the domain of oil and gas chemistry, palladium serves as a catalyst for hydrogenation/dehydrogenation, facilitating the production of high-quality fuels, monomers for the polymer industry, and aromatic compounds. In the field of pharmaceuticals, palladium is employed in the synthesis of drugs that exhibit anti-inflammatory, antiviral and anti-cancer properties. In fine organic synthesis, palladium is used for the production of pesticides, herbicides, food additives, dyes and polymers.

Furthermore, palladium’s role in electrolysis technologies is significant, particularly in reactions involving metal reduction from electrolytes, and oxidation of chlorine and chlorine-containing compounds. Fuel cells are also employed in reactions of oxygen and hydrogen extraction.

Palladium, akin to other noble metals, exhibits elevated chemical resistance (see ‘Chemical properties’ table). It demonstrates negligible reactivity with acids and alkalis, with the exception of concentrated nitric acid and aqua regia. This characteristic endows it with corrosion and oxidation resistance in a multitude of environments. It maintains its properties when exposed to moisture, oxygen and other corrosive substances. This attribute makes palladium a valuable material in various industries, particularly in the development of corrosion-resistant and biocompatible alloys for diverse applications.

Properties: Physical and mechanical

The unique physical and mechanical properties of palladium are determined by the structure of its crystal lattice and the electronic configuration of its atoms. These properties, in turn, determine the metal’s behaviour under the influence of physical factors, such as density, melting point, electrical and thermal conductivity, magnetic properties, and coefficient of thermal expansion (see ‘Physical properties’ table). Among the properties of palladium are:

It possesses the lowest density, melting point and temperature coefficient of electrical resistance among platinoids.

Its heat capacity, thermal expansion coefficient and magnetic susceptibility are the highest among platinoids.

Physical properties

| Property | Pd | Pt | Ru | Ir | Rh | Os |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density, g/cm³ | 12.02 | 21.45 | 12.41 | 22.65 | 12.42 | 22.61 |

| Melting point, ℃ | 1552 | 1768 | 2334 | 2466 | 1963 | 3033 |

| Heat capacity, J/mol·°К | 25.9 | 25.8 | 24 | 25.1 | 25 | 24.7 |

| Thermal conductivity, W/m·К | 71.2 | 69.1 | 116 | 147 | 151 | 91.67 |

| Coefficient of linear expansion, K−1 | 11.2·10−6 | 9.0·10−6 | 9.1·10−6 | 6.5·10−6 | 8.44·10−6 | 7.3·10−6 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (20 °C), | 5.231 | 0.9712 | 0.427 | 0.133 | 0.9903 | 0.0052 |

| Electrical resistivity, µOhm·cm (0 ℃) | 9.76 | 9.82 | 6.16 | 4.67 | 4.43 | 8.07 |

| Temperature coefficient of electrical resistance (0–100 °C) (10−3 K−1) | 3.77 | 3.927 | 4.10 | 4.27 | 4.3 | 4.10 |

Palladium is used in electronics to create corrosion-resistant electrically conductive coatings for contacts and wires, due to the combination of relatively good conductivity and high corrosion resistance.

It is noteworthy that the electron shell structure of the palladium atom exhibits the highest magnetic susceptibility among platinoids, surpassing other PGMs by more than fivefold (see ‘Physical properties’ table). This property enables its utilisation in alloys with iron and cobalt in contemporary information storage devices. The giant magnetoresistance effect makes palladium a promising material for application in magnetic memory devices, sensors and other spintronics devices.

Palladium occupies an extreme position among the platinum group metals. It has the lowest strength, hardness and modulus of elasticity, but has one of the highest degrees of relative elongation, which characterises its ductility (see ‘Mechanical properties’ table).

Mechanical properties

| Property | Pd | Pt | Ru | Ir | Rh | Os |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile strength, MPa | 190 | 250 | 500 | 623 | 420 | – |

| Relative elongation, % | 40-42 | 41 | 3 | 6 | 9 | – |

| Young’s modulus of elasticity, GPa | 121 | 168 | 447 | 528 | 275 | 570 |

| Vickers hardness, HV | 50 | 55 | 250 | 200 | 130 | 300 |

The utilisation of palladium in numerous domains of mechanical engineering and metallurgy is predominantly driven by its physical and mechanical properties, particularly its capacity for heat and corrosion resistance. The alloy’s remarkable ductility, evidenced by a relative elongation of up to 42%, is comparable to that of platinum, which reaches a relative elongation of up to 41%. This attribute confers upon palladium the remarkable ability to withstand various forms of deformation without fracturing. Additionally, its low density enhances its economic viability.

Cold deformation of 99.99% pure palladium results in its gradual hardening by up to 2.5 times, while its plasticity decreases more sharply and already at insignificant compression values the relative elongation does not exceed 5–8%. The combination of these qualities makes it possible to produce parts of complex shapes by various methods of rolling, stamping and other processing methods, controlling the mechanical properties of products in a wide range of values.

Palladium-based alloys find applications in the fabrication of special chemical utensils, medical instruments and, indeed, high-quality musical instruments. Another application of palladium alloys is in dental implants and other prosthetic structures in dentistry, where both its mechanical characteristics and its chemical inertness are important.

Special chemical properties

Notably, palladium exhibits the distinctive property of absorbing hydrogen at a volume 900 times that of its own, a capacity attributed to its unique atomic structure. During the sorption process, hydrogen is not only deposited on the palladium surface but also migrates into the lattice inter-nodes, facilitated by the optimal interatomic spacing and shape of the electron clouds. It is hypothesised that palladium hydride (PdH) is formed during this process. The precise structure of the resulting compound, however, remains to be elucidated. When the volumes are converted to masses, the utilisation of palladium in this particular variant appears disadvantageous, as the masses of the stored hydrogen and the carrier become nearly equivalent. However, if palladium is utilised not as bulk material, but rather as a nanofoam with a very small density, then new prospects for the use of this metal for hydrogen storage become apparent.

Consequently, palladium is a subject of active research in the field of hydrogen storage and purification systems. Palladium is also a crucial metal in the production of membranes for hydrogen purification, with these membranes being utilised to produce hydrogen with a purity of 99.99999%. This exceptional purity is attributable to palladium’s distinctive capacity to selectively diffuse hydrogen through a crystal lattice through which no other gas can pass.

The unique properties of palladium, including its lightness and ductility, inertness and corrosion resistance, sufficient chemical activity, catalytic activity, good electrical conductivity, high thermal conductivity and high melting point, make it a valuable material for use in a variety of applications.